Indeed, the

mechanical appliances for finishing and adjusting different

parts, comprise one of the most interesting departments of the

works, with their planting machines, lathes, punches,

screw-cutting tools, grinding and polishing stones, and drills

which allow of the drilling of several holes in the same piece

at the same time, and at various angles.

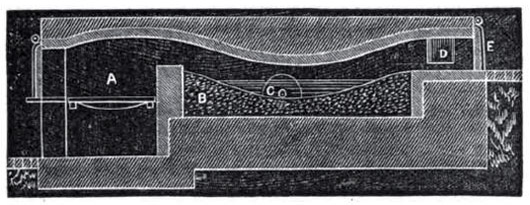

The pig iron

used preferably for malleable castings is a white charcoal pig,

and is melted in cupolas, or in a reverberatory furnace (picture

below).

This latter

furnace, of which A is the fire-place, B the hearth, 0 the

tap-hole, D the flue towards the stack, and E the door through

which the impurities are removed from the top of the molten

metal, consumes more fuel, and produces more waste than the

cupola. On the other hand, the metal is purer, because it is not

melted in direct contact with the fuel, and does not absorb its

impurities, sulphur especially. There is also the advantage

that, should the metal contain too much carbon, part of it may

be removed by the oxidizing action of the flame.

Most of the

castings are made in green sand, from metallic patterns, which

insure constancy of shape and of smooth surfaces.

The castings,

which are as brittle as glass, are then put into "tumblers,"

which are revolving cylinders of cast-iron with ribs inside, in

which the articles are deprived of adhering sand, and become

polished by mutual friction.

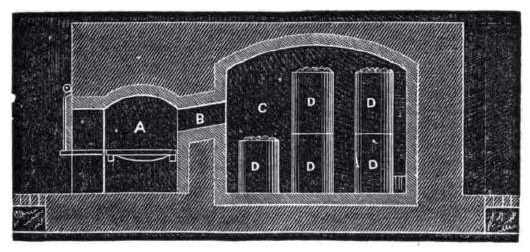

The cleaned castings, intended

for conversion into malleable iron, are next packed close, with

alternate layers of powdered iron scales from rolling-mills,

into rectangular cast-iron boxes D (engraving below), which

become of a rather elliptic shape, after a certain length of

use, and which can be placed one upon top of the other, if need

be, and closed at the top by a mixture of sand and clay which

prevents contact with the air, and follows the settling of the

mass.

Engraving above represents the disposition of

the annealing furnace, which resembles those employed for making

the bone-black of sugar refineries. A is the fire-place, B a

flue conducting the flame into the annealing chamber C; and D D

D are the cast iron boxes filled with the iron scales and the

articles to be softened.

Leaving aside the time necessary for raising the

temperature, and the cooling off, the articles are subjected for

about a week to a white heat, not sufficient, however, to melt

what may still remain of cast-iron.

After a proper annealing, the castings are

covered with a film of oxide of iridescent colors - the yellow

and azure blue predominating - which resembles that kind of

Champlain iron ore called peacock, on account of its coloration.

Any adherent oxide is removed by another passage

through the "tumblers," and the process of malleable iron making

is finished. Any further grinding, polishing, boring, and

adjusting which may be needed, is made in the same works.

The oxide of iron, or scales, employed, have

parted with a portion of their oxygen during the annealing

process, and the loss is made good by grinding the scales, and

rusting them with a solution of sal ammoniac (hydrochlorate of

ammonia).

It seems to us possible to do without the

expense of sal ammoniac, by wetting the powdered scales several

times with water, stirring and drying them on the top of the

annealing furnace.

Among the products manufactured by the above

mentioned firm, we have noticed hinges, entirely of cast-iron,

and others with wrought iron pivots; patent elastic washers for

railroad fish-plates, which prevent the nut from unscrewing, and

keep it tight; castors for furniture, bolts, pulleys for cords

of window sashes, keys, padlocks, screw presses, carriage parts,

saddlery hardware, &c. &c. In fact, it would be necessary to

make a catalogue with an index, of all of the patterns which

were shown to us.

It is difficult to state the cost of malleable

iron castings, since it depends to a great extent upon the size

and the quantity of the articles. We may say, however, that

being given a certain pattern, the malleable iron castings will

cost from 70 to 80 per cent, more than ordinary castings from

the same pattern. This increase of price is necessitated by more

labor, the consumption of fuel for annealing, greater cost of

pig metal employed, &c. &c.

To sum up, malleable iron castings are useful,

whenever equal strength of material being not needed, the cost

in labor, if made of wrought iron, would be too great; or when a

casting is needed without the brittleness of common cast iron.

Scissors, sewing-machine parts, the butt-ends

and guards, and many other parts of gun locks, ornaments, &c.

&c, are made in quantities from malleable iron castings. Even

nails, of all sizes, are thus manufactured in England, and we

are disposed to believe that, if made of good metal and well

annealed, they may be at least equal to certain cut-nails

produced from inferior plate, and the fiber of which has been

broken by the concussion of the cutting machine.

Oxide of zinc has been proposed as a substitute

for oxide of iron, under the plea that the operation is more

rapid.