The manufacture of malleable

iron castings is older than is generally thought, although the

knowledge of the true principles on which it is based dates from

the more recent period of the establishment of chemical science.

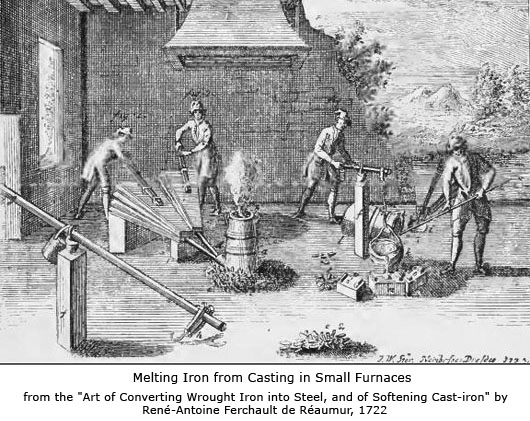

In his work on the "Art of Converting Wrought Iron into Steel,

and of Softening Cast-iron" (Tart deconvertir le fer forge en

acier, et Tart d'adoucir fe fer fondu), published in 1722,

Reaumur gives the numerous experiments by which he succeeded in

producing malleable iron castings, which had already been made

some twenty years before, but in a secret manner.

The manufacture of malleable

iron castings is older than is generally thought, although the

knowledge of the true principles on which it is based dates from

the more recent period of the establishment of chemical science.

In his work on the "Art of Converting Wrought Iron into Steel,

and of Softening Cast-iron" (Tart deconvertir le fer forge en

acier, et Tart d'adoucir fe fer fondu), published in 1722,

Reaumur gives the numerous experiments by which he succeeded in

producing malleable iron castings, which had already been made

some twenty years before, but in a secret manner.

At the epoch in

which Reaumur lived, the true era of chemistry had not yet

begun, the relations of carbon to iron in pig metal were not

known, and the various degrees of hardness and appearance in

cast-iron were attributed to the presence of various impurities,

sulphur especially.

After many

experiments with all kinds of substances and salts - the results

of which were noted with a remarkable acuteness of observation -

Reaumur succeeded in his purpose with three different mixtures.

Having observed

that a plate of cast-iron, exposed for a long time to the direct

action of a fire, was covered with a coat of black and red

oxide, and that the metal underneath had become softened

(malleable), he collected such oxide for the purpose of packing

with it small bars of white cast-iron, and after heating them in

covered crucibles, he obtained a perfectly malleable iron. His

other mixtures were powdered limestone and charcoal, and

charcoal with calcined bone-dust.

The first

mixture is evidently that used at the present time; the second

may be explained by the oxidizing action, at a certain

temperature of the carbonic acid disengaged, which parts with an

atom of oxygen (CO2 + C = 2 CO) combining with the carbon of the

cast iron, and which becomes carbonic oxide. In the third case,

we may surmise that the carbon was burned out by the air of the

fire-place, penetrating through the interstices of the cast iron

plates forming the boxes in which the metal and the mixture were

packed.

The air was

prevented from acting violently by the mass of bone-dust and

powdered charcoal with which the articles were surrounded. We do

not believe that the temperature was sufficiently high to

decompose the bone dust, even in presence of the charcoal.

The furnace

employed was of brick, and square, and divided by vertical

partitions of cast-iron plates, between two of which were packed

the castings and the mixture, and around which were flues far

the circulation of the gases of the fire-place.

However

imperfect these dispositions may be when compared with the

present ones, Reaumur ascertained that oxides of iron and

cast-iron, heated together in closed vessels, produced malleable

iron; that for malleable castings, white is preferable to gray

metal; that the castings, previous to annealing, should be

deprived of the adhering sand, which becoming fluxed, prevented

the reaction; that too protracted and too intense a heat may

harden the castings again; and that properly annealed articles

may be bent, forged, welded, case-hardened, and present all the

properties and even appearance of wrought iron.

After having

explained the principles upon which the industry of malleable

iron casting is founded, and given a historical notice of the

first trials made, we cannot do better than to describe the

actual processes, such as are applied at the Hardware and

Malleable Iron Works of Messrs. Chas W. Carr, Jos. S. Crawley,

and Thos. Devlin, successors to E. Hall Ogden, and whose store

is at 307 Arch Street, Philadelphia.

In this large

establishment, where everything is conducted with the best order

and understanding, anything in the line of ordinary and

malleable castings for building and cabinet, carriage and

saddlery hardware, &c., is made complete, from the pattern to

the casting, annealing, coppering, adjusting and japanning of

the articles.